FIVE ALLEGORY OF THE NEW MOSKOVITES

“Nowhere nothing, no place never.” Velimir Khlebnikov

Abstracts

This article deals with one of the directions of the modern domestic art process, which is of interest as a characteristic case of contemporary culture. The description and documentation of the activities of the “New Moscovites” group can be considered as valuable preparatory material for further research of a general type.

Keywords

Contemporary art, Moscow school of painting, Russian art, art theory, history of painting, Moscow artists, contemporary artists.

Why “allegory” and who are the “New Muscovites”? Let's start with the second question. The term “Muscovites” has long been used in relation to citizens of the Grand Duchy of Moscow - Muscovy (the original Latin name of Moscow, which was later transferred in a number of Western European states to the unified Russian state formed around Moscow under Ivan III). In our case, we are talking not so much about the geography of residence of artists (although this, of course, matters), but about the artistic and creative methods of the Moscow Art School, as a direction in Russian art. These Muscovites are new not only because they live in the present time, when this term is no longer used in relation to the residents of Moscow, and especially our entire state, but also because, being continuers of Moscow artistic traditions, they reflect current trends in their work. problems of our time, trying to find new means of artistic expression.

Before talking about the allegories themselves, let us dwell on the Moscow school of painting itself, in which this very allegory has always been of great importance, and the concept of which was fixed in relation to several generations of Moscow painters, starting from the end of the 19th century, who gravitated in their work to a wide range of traditions the old Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, with which almost all Moscow artists were in one way or another connected during the eighty-five years of its existence (from 1833 to 1918). Some studied there, others taught, and many both studied and later taught. Of course, art in Moscow arose much earlier, but it was with this period that the most significant names of artists of the realistic movement in Russian painting are associated, and it was the emergence of this institution that “materialized” the rivalry and, to some extent, the confrontation between two Russian art schools: Moscow and St. Petersburg.

The Moscow School differed favorably from the St. Petersburg Academy in its greater democracy, freedom of artistic creativity and responsiveness to new, advanced trends. Moscow artists, although they were financially constrained and lacked state support, nevertheless developed in a more lively and free creative atmosphere, not being limited in their quest by academic recipes. And although “there was a lot of handicraft and imperfection in the system and methods of teaching at the School, especially during the period of its inception,” from the very beginning it was dominated by “an atmosphere of active love for art, interest in public life, friendly relations between teachers and students and active tension in their joint efforts,” which “gave a serious tone to the work of the School and contributed to the success of students.”

All these circumstances could not but affect the nature of the work of Moscow artists: expression and emotionality, rebellion and genuine reproduction of life became the hallmarks of the Moscow school of painting, and its roots in icon painting and closeness to ornament and decor gave it an inimitable picturesqueness, symbolism and the power of unity of truth and beauty. “Since the time of Perov, the right, lively tone for the matter has been set. Lately there has been a lot of artistry. This young, simple and unique school exuded life! ...now it is becoming clearer and clearer that Moscow will gather Russia again. In all the most important manifestations of Russian life, Moscow expresses itself in a gigantic manner, inaccessible to other cultural centers of our fatherland; they only have to imitate it, and on a more modest scale. Yes, Moscow will take its toll in the school of painting...”

In 1918, the Moscow art school ceased to exist as the School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture and was first transformed into VKHUTEMAS, on the basis of which the Moscow Art Institute subsequently grew. V.I. Surikov, who gave a huge galaxy of Moscow artists of the Soviet era, who made a significant contribution to the general treasury of Russian fine art, defining the main creative trends in the fine arts of this period on the basis of the democratic traditions of progressive Moscow art of the 19th century. More than one work will still be written about the role of VKHUTEMAS in Russian art and design: despite the fact that its life was short, it left behind a significant legacy.

Moscow art has always been closely connected with real life and human experiences. During the Great Patriotic War, many Moscow artists volunteered for the front, while others actively participated in propaganda work, creating posters and sharp political satire. In the 60s, the social changes taking place in our country gave rise to an active movement in the fine arts among the youth of that time, the pathos of which was an appeal to the harsh romance of the post-war years, giving rise to a whole galaxy of well-known artists. In the 80s, along with easel types of creativity, there was a growth in decorative and applied and monumental art, scenography, design, applied graphics and posters. And in all these areas, Moscow masters largely “determined the weather” and had a decisive influence on the development of the arts far beyond the capital. Along with official art, Moscow conceptualism and Moscow actionism arose at this time, brands that, unlike the Russian avant-garde, are better known abroad than in the vastness of our vast Motherland.

The events of the 90s turned the life of the entire country upside down, and Moscow artists were no exception: the problems of identity and “institutional search on the world art scene coexisted in the 90s with reflection on the possibility of art as such and the search for its alternative forms, united by the critical strategy of the emerging political art ". Against the background of conservatively oriented artists, quotes from Moscow actionists, artists who broke with ambitious claims to isolation in the system of social hierarchy and renounced the role of producers of “supervalues,” looked like radical and aggressive attacks against artists who defended the position of preserving the autonomy of art. The unique place of contemporary art on the border with philosophy, politics and visuality has changed the Moscow artistic landscape, giving rise not so much to new movements and creative unions, but to individualism and self-expression. However, even under these conditions, the Moscow art school retained its originality.

The 2000s still retained “the energy of change, post-shock neuroticism, openness to the new and that amusing naivety with which many of us expected from contemporary art, if not accomplishments, then an unknown future,” and in the 2010s fatigue set in: from institutional routine, festival leapfrogs and instability. The previous decade began with the success of artists following their own path in art, outside of groups and movements, but then it turned out that being a loner was no longer fashionable. The current Moscow art world is diverse and heterogeneous. Along with successful individual artists, various art galleries are actively trying to operate there, uniting certain authors under their mother brand, usually based on the personal taste of the gallery owners or the sales potential of the works.

In this regard, the New Moscovites Art Group is a unique project that unites five independent contemporary artists who are representatives of the Moscow art school in its broad meaning and deep sense. Two of them, Vladimir Ozerov and Yana Gavrilkevich, are graduates of the Moscow State Academic Art Surikov Institute, that, as already mentioned, is the direct heir of the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Vitaly Kopachev and Anatoly Pelevin, in turn, graduated from the Moscow Institute of Technology, where they received their art education ten years apart. Antonina Garasko studied drawing and painting at the Moscow Pedagogical State University and is currently a teacher at the Moscow State Academy of Arts. Surikov. They are all very different in their vision of modernity, the artistic techniques and styles they use, but their work is based on the basic principles that characterized the Moscow school of painting from the moment of its inception. And the allegory to represent their work was also not chosen by chance.

We have already discussed the rootedness of Moscow art in icon painting with all the ensuing consequences. Unfortunately, Moscow frescoes and icons of the 12th-13th centuries have not reached us, but already in the works of the early 14th century - the icon “Boris and Gleb” and the miniature of the so-called Siya Gospel - we can see the pure sound of bright open colors and graphic expressiveness of flat silhouettes. In another monument of the mid-14th century - the icon “Nicholas with the Life” - “in its decisive sweeping manner of painting and its very special psychological structure, one can feel the hand of a master who is not very accustomed to taking into account models”. Isn't it true that the characteristics are familiar? Already this “primitive” had its own, clearly expressed face, in which one senses extraordinary freedom, simplicity, emotionality, naturalness and vitality, which were a distinctive feature of Moscow painting throughout the entire period of its existence. Even subsequent “European influences”: from Byzantine painters to the movements of the 20th century did not destroy this originality, deeply rooted in the style of the Moscow icon, “with its light graceful figures, with its dynamic compositions, with its bold color comparisons.”

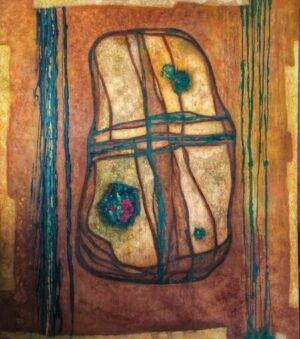

Moving on to a direct description of the allegorical works of the New Moscovites, it should be noted that at the center of any type of art is a person, his experiences, feelings and passions. Art itself is nothing more than an emotional-imaginative exploration and expression of the reality surrounding a person. And it is man, his essence of creation and creator, who appears before us in the form of a stone in Vladimir Ozerov’s canvas “The Solovetsky Stone”. (p. 1). The place where the work was written is the famous Solovetsky Monastery, and the meaning of the work is a vivid and strong illustration of the famous philosophical “stone paradox,” which for a long time remained unsolvable. Its essence is whether Almighty God can create a stone that he himself cannot move. The whole point is that if God can create such a stone, then he is not omnipotent, since he cannot move it from its place. The creation of such a stone is the limit of divine omnipotence. But if God cannot create such a stone, he is also not omnipotent, since the creation of some things becomes impossible for him. The paradox of the stone belongs to a family of paradoxes associated with various interpretations of the concept of omnipotence and arising from the idea of an omnipotent being capable of setting impossible tasks for himself or embodying logically contradictory verbal constructions in objective reality, such as, for example, the “square circle.”

The answer to the “paradox of the stone” depends on what philosophical and ideological positions the answerer takes. A believer will not doubt God’s omnipotence for a second and will say that God is so omnipotent that he may not become omnipotent for a while. A physicist will note that this formulation of the paradox is vulnerable to criticism due to the inaccuracy of terms that refer to the physical nature of gravity: for example, the weight of an object is determined by the force of influence of the local gravitational field on it. The logician will argue that it cannot be formulated without a logical contradiction: either the subordination of God to the world, or the removal of a phenomenon inherent in our world beyond its borders, or the absence of God. The logical contradiction lies in the fact that the terms “lift” and “stone” are intraworldly, and God can create a stone that no one in this world can lift, but God himself can “lift” it - since he is not subordinate to the world and “lift” - only an internal observation of the process.

Looking at the work of Vladimir Ozerov, “The Solovetius Stone,” we understand that no matter how heavy the “stone” is and no matter what bonds bind it, it is capable, if not of being lifted by someone, then certainly of rising itself. The stone lies on the ground, entangled in its worldly connections and wounded by its passions, but what “torments” it is also what lifts it up. This is told to us by the joyful turquoise color, common for “fetters”, “wounds” and vertical stripes, symbolizing the path “up”. This path is very difficult, but from birth a person has a desire for light and a love for beauty, despite the fact that his life is often associated with trials and suffering that leave deep wounds in his soul. Nevertheless, these wounds are the key to enlightenment and salvation of the soul, and who knows this better than the monks, including those in the Solovetsky Monastery.

The question of the origin of man and the universe as a whole is one of those to which humanity has been seeking an answer throughout its existence. What happened first: the chicken or the egg? Until now, no one has given a convincing answer to this simple riddle. Antonina Garasko’s work is called “The Sun,” although at first glance it may seem that it is just an egg in the form of a fried egg. (p. 2) However, if we look at the canvas more closely, then beyond the edges of the “curdled protein” we begin to see an endless blue-black space, in which the lonely Sun shines brightly, giving light, warmth and food to all life on Earth. Egg-sun or Sun-egg? Both one and the other can “give life” and “feed”, and can also kill.

In Egyptian mythology, the egg represents the potential for awakening life and is a symbol of immortality. The egg contains the great secret of the creation of the world and the preservation of eternal life. The Indian Vedas tell of a golden egg from which Brahma hatched. The legends and myths of many countries of the ancient East tell that there was a time when chaos reigned everywhere in the Universe, and this chaos was located in a huge egg in which all forms of life were hidden. The shell of the egg was warmed by divine fire, and the mythical creator Panu was born from the egg. The Creator connected the weightless Sky with the solid Earth, created space, wind, the Sun, the Moon, clouds, thunder, lightning.

In ancient Russian tales of Koshchei the Immortal, the egg represents a secret repository of life and death and is kept under seven locks and seals. For our ancestors, the egg served as a symbol of life, a symbol of the awakening of life, the beginning of a new day, the arrival of which is heralded by a rooster - a symbol of the awakening sun, which since ancient times has been, first of all, a symbol of creative energy. For many peoples, solar deities were the strongest and most powerful. The sun is the giver of light and life, the ruler of the upper and lower worlds, which he goes around during his daily circulation.

Human life is inseparable from creativity. It is creativity, with its emotional, imaginative and artistic reflection, that elevates a person above everyday life and distinguishes him from the rest of the animal world. “The Crown” by Anatoly Pelevin is exactly about this. (p. 3). The work is based on the famous image of a crown by Jean-Michel Basquiat, who created his “Crown” in 1983 in the style of neo-expressionism and street art using ink and acrylic on paper covered with sheets of notes and sketches. The crown, in principle, is the most popular symbol in the work of Basquiat, who went from a tramp to a famous and expensive artist. Often it denotes the high intellectual and spiritual merits of the represented character. Being depicted on its own, without any connection to a specific person, it becomes a sign of chosenness and greatness.

Anatoly Pelevin depicted the Crown on a rusty background as a symbol of today's times, in which people strive to become famous and “starry”. On the one hand, this is the scourge of our days, giving rise to many unusual and even unpleasant moments for professional representatives of one or another field of activity. In the digital world, anyone can become famous in a short period of time without even putting much work into it. The main thing is to find a response in the soul of the audience. On the other hand, everyone has the right to their “minute of glory”, investing their soul and time into their creativity, doing what they love and constantly improving in it. The artist is confident that absolutely anyone can become a “king” in their business and remain so in eternity, even when everything collapses and rusts. At the same time, the ironic and primitive way of depicting the crown itself reminds us that we should not take the glory and status of the king too seriously.

Yana Gavrilkevich’s work “The Garden” represents an allegory of the happiness that a person lost by leaving the Garden of Eden, and to which he inevitably strives throughout his life. (p. 4). We can judge that the canvas depicts happiness, first of all, by the color scheme of the work: yellow, red, green, blue and white are the colors associated with this emotion for most people. According to psychophysiologists, each of us feels colors on an intuitive level. What ancient color therapists only guessed about, modern medicine has established absolutely precisely: this or that color, acting on the iris of the eye, thereby reflexively affects the vital functions of all our organs, changes the physiological background of a person, affecting the state of his nervous system and causing hormonal changes in the body. The very manner of writing the work, despite the presence of diagonals, does not cause anxiety - it is a calm and balanced movement along a familiar route that does not threaten us with any cataclysms

Apples and an angel in a red robe with luminous colored wings tell us about the Garden of Eden, as the quintessence of happiness. Everything breathes peace and joy, awakening corresponding feelings in the viewer. Red and yellow colors create in those who look at them or wear them a feeling of coziness, comfort, relaxation, peace, and evoke a feeling of closeness and emotional attraction. In turn, blue and green relieve tension and stress, creating a feeling of harmony both within a person and in his relationships with the outside world. Isn’t this an idea of the happiness of a modern person, mired in a competitive and conquest lifestyle, an abundance of information and superficial communication, and at the same time isolated from nature and his own kind?

It is about the loneliness of modern man that Vitaly Kopachev’s work from the “Phantom Goals” series tells us. (p. 5). “Everything is ghostly in this raging world, there is only a moment - hold on to it,” is sung in a famous Soviet song. A person comes into this world alone and leaves it alone. Between these moments his life flies by like a stormy stream of emotions and a whirlpool of events. Sooner or later, each of us is forced to stop and look inside ourselves.Everything around is seething and seething as before, but the person who dares to face his transcendental loneliness will never be the same. At this moment, everything happening around becomes distant and largely unimportant, although still dear and familiar.

The colors of the canvas also seem to be bright, but how strikingly different their language is from the previous work. This is not at all the yellow that tells us about joy and happiness, and earthy green does not calm us down at all, but rather, on the contrary, instills anxiety, which is only intensified by purple, black and brown. To top it all off, beige, gray-white and pale lilac sing their sad song. Sharp strokes in different directions speak of confusion and chaos in the soul of a person who has realized that he is alone. And at the same time, hard dark vertical spots give reason to think that a person will resist, accept his path and walk along it to the end, to where the stones are light, life is endless and everyone walking in the Garden of Eden has his own crown, crowning a happy soul.

Bibliography

1. Dmitrieva N., Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. M., 1951. 2. Lazarev V.N., Moscow school of icon painting. M., 1971. 3. Podobedova O.I., Moscow school of painting under Ivan IV. M., 1972. 4. Repin I.E., Letters. Correspondence with Tretyakov. M.-L., 1946. 5. Savitsky S., Kolobok Malevich and others. A view from St. Petersburg on contemporary art of the 2010s. St. Petersburg, 2021.

ILLUSTRATIONS

(p. 1) Vladimir Ozerov. Solovetsky stone. Canvas. Acrylic. 130x150 cm. Private collection.

(p. 2) Antonina Garasko. Sun. Canvas. Oil. 100x100 cm. Private collection.

(p. 3) Anatoly Pelevin. Crown. Canvas. Mixed technique. 75x45 cm. Private collection.

(p. 4) Yana Gavrilkevich. Garden. Canvas. Oil. 90x60 cm. Private collection.

(p. 5) Vitaly Kopachev. Series "Phantom Targets". Canvas. Mixed technique. 120x80 cm. Private collection.